At the start of 2022, ScienceBusiness gathered feedback from an online survey and meetings with its member organisations on how they managed the 1st round of Horizon Europe Call applications. As part of that effort, I moderated a dedicated session of the ScienceBusiness network to compile researcher experiences as well as comments from many academic and industrial research support offices. The result: a new – free – White Paper with recommendations to the European Commission on how to make the next six years of Horizon Europe even better. The White paper, which I co-authored, will be presented to Director-General Paquet during the online Business Annual Network conference on the 8th February.

Essential Guide to understanding the Horizon Europe Programme

I co-authored the latest (4th) edition of the “Essential Guide” to understanding the Horizon Europe Programme. In the book, available from the ScienceBusiness website, we explain what this programme is about and how academic and industrial researchers can benefit from it. It is an easy-to-read, yet authoritative, guide to the programme. In plain language, with the complexities deciphered. The report includes new analysis and data on the programme, as well as quick summaries of key news milestones along the way towards the programme’s start. The report describes:

- How the programme is structured and budgeted

- The latest Horizon work programmes – up to September 2021.

- What’s new since the last programme, Horizon 2020.

- Who can participate, and how.

- How the programme came together politically, with what objectives.

- What it means to the rest of the world – and how researchers from Canada to Japan could benefit.

- How it tries to fix the east-west innovation gap.

- Tips for applying.

- Its missions, partnerships and sectoral clusters – in health, space, digital, agriculture, energy, climate, culture and more.

- Its three big funding agencies: ERC, EIC and EIT.

Publication: the ATTRACT concept – removing innovation serendipity

In the summer of 2014, my colleague Dr. Pablo Garcia-Tello, Dr. Markus Nordberg (who was Resources Coordinator of the ATLAS project at CERN at the time), Dr. Marzio Nessi (who was then still overall technical coordinator and ATLAS project manager) and I started discussions on a new way of fostering breakthrough innovation that would do away with the typical serendipity conundrum. In many organisations, innovation is not a sustained and planned process; instead it is highly dependent on available time, money, capacity, management priority and many other factors. Public grants can act as innovation-facilitators, but in most cases the innovation stops as soon as the grant money is used up. It is then back to square one: applying for new grant funding, and convincing management that capacity and money will prove to have been well-spent…one day. This innovation serendipity conundrum leads to unnecessary waste of money, time and capacity. Moreover: it does not help society at large in meeting many of its challenges.

Our discussions centred on matching three concepts:

- streamlining of the breakthrough innovation process by coupling fundamental research at Research Infrastructures and their associated communities to private and public actors that can extract societally relevant innovations from them;

- introducing a co-innovation approach that allows truly joint and equal partnership collaboration between scientific and industrial communities;

- generating breakthrough innovation in a non-linear fashion by identifying the right combinations of breakthrough technology options that would sufficiently interest investment communities to start help push the innovation beyond the well-feared innovation ‘valley-of-death’.

The result was a proposal submitted by a group of European Research Infrastructures, a business university, a design-thinking university and an industry association, to the European Commission. That proposal, under the name ATTRACT, was highly successful in validating our three-step approach, and has since led to a sequel project in which game-changing innovations are guided in a sustained way from their basic science foundation to concrete societal applications. You can visit the ATTRACT website by clicking here.

You can also read our publication: ATTRACT-1 publication

Digital Innovation Hubs in H2020: do you know what they are?

The H2020 Work Programme 2018-2020 is open; if you’ve had a look inside, you may have come across something called a ‘Digital Innovation Hub’ (DIH). Ever wondered what these are? I have.

Of course, there is information on the European Commission website and even some of the active DIHs provide some insight on what they are, but still I found it difficult to see what to do with them in some of the Work Programme Call topics. And as a consultant, I should – of course – know. So here is my summary in bullet-points. Any additions or corrections are welcome, but this post is primarily meant to (also) get other people started thinking about a DIH proposal.

Background to Digital Innovation Hubs

- DIHs are one-stop shops where SME companies can go in case they have an innovation they wish to test/validate/upscale but do not have the knowledge or technical capacity/infrastructure themselves to do it.

- DIHs are supposed to act as the centre of a regional co-system around a particular theme/domain (examples: robotics, or additive manufacturing).

- DIHs are primarily created by regional authorities and/or regional development agencies, who have identified a particular theme/domain in their Smart Specialisation Strategy (S3). Currently there are already some 450 DIH active across Europe (see: http://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/digital-innovation-hubs-tool).

- Most regional DIH are funded at national/regional level through the Structural Funds. An operational DIH is a regional multi-partner collaboration of universities, RTOs, industry-representation, regional development agency and regional government authority. In addition to facilitating testing/validation of innovations by SME companies, a DIH also has the explicit aim to create a network and thus help improve the overall competitive position of these companies in their region within the theme/domain.

- DIHs can also be set up via a direct application to the ESIF (“European Structural and Investment Funds”, which combines Structural Funds, ESF and Common Agricultural Fund money).

- Several so-called DIH initiatives are also already running. These initiatives are paid directly by the European Commission as so-called CSA-projects in H2020. Their main aim is to help create further regional DIHs. They provide training and support in the organisational setting up of a new DIH. One such example is: i4MS.

DIH in the H2020 Work Programme 2018-2020

The EC provides direct support for the development of DIHs (€100 million p/a) within the H2020 Work Programme 2018-2020 in the following two ways:

- As CSA consortium projects, whereby DIHs in the same theme/domain but in different regions work together to (1) make publicity (dissemination) for innovation results by the companies that worked with them, (2) create a cross-border network on a theme/domain which allows companies to expand their network and work better together to maximise synergies.

- As IA consortium projects. In this case, the EC stipulates in the Work Programme in which theme/domain it expects the creation of a new DIH. The difference to what has been written above, is that in this case we are not talking about a regional DIH, but a cross-border (virtual) DIH of knowledge and capacity. In practice: this means universities, RTOs and large companies in different countries jointly providing access to their knowledge and infrastructure for validation/testing of innovations (as suppliers!). The level of ambition is high: the consortium must be highly specialised (knowledge, technical capacity) and/or have very expensive technical equipment available which smaller companies would never be able to afford. I would find it likely that such a consortium would also comprise one or more regional DIHs in the same theme/domain so that there is a natural link to regional industrial activities.

One thing very specific to IA-DIH is that they should transfer at least 50% of their own funding to the SME companies who want the consortium to perform a test/validation using their infrastructure. The model for doing this is called the ‘Third Party’-support model based on section K in the General Annex of the Work Programme (luckily, I already have experience working with this model, so that helps to understand how this works). In other words: the DIH-consortium will need to open Calls for Tender to which companies can apply. The consortium then decides which of the consortium members is best qualified and is available to perform the testing/validation.

A DIH-IA grant application does not have to be directly connected to an existing regional DIH, but I think this is advisable. The IA-consortium should – in any case – work toward the creation of new regional DIH is that same theme/domain so that (1) more companies gain access to infrastructure and knowledge they otherwise could not afford; (2) more companies gain access to a much bigger network of other regionally based SMEs that may provide new innovation opportunities.

The final question that remains is: so who should apply for funding in H2020 topics related to DIH? In my view, universities are probably the best placed to lead these projects. A consortium should also contain one or more RTOs and one or more regional DIH (as evidence that the proposal is founded in existing S3 initiatives). Alternatively, it could comprise a regional authority/development agency who has the stated intention (in their regional development plan) to create a regional DIH. Lastly the consortium should also comprise several larger companies that can also act as suppliers of knowledge or infrastructure to carry out the testing/validation/upscaling for the applicant SMEs.

Proposed schedules for Interim Payments in FP9 are a recipe for more tensions within project consortia

Many scientists across Europe with high research and innovation ambitions will have started the new year with some close reading of the recently published – and last – H2020 Work Programme. In the meantime, the European Commission as well as hundreds (if not: thousands) of lobbyists are already heavily engaged in discussions on the contours of the next European Research Programme, currently still called Framework programme 9 (FP9).

As the most sensitive part of these discussions – the budget for the whole programme – is about to start with many ideas, suggestions, rumours and counter-rumours happily making their rounds through the lobby-carrousel, some other – more concrete and even operational – approaches are already actively being communicated by the Commission to the various national contact points.

One of these approaches concerns the Commission’s intention to increase the use of lump-sum financing (*) of projects. The basic idea behind that is that this mechanism – which includes maintaining the flat 25%-rate for the calculation of indirect costs (e.g. overheads) will continue the Commission’s drive toward more simplification of financial and administrative project management as well as to reduce the risks of fraud from wrongly claiming personal costs (from my experience this is mainly caused by the cumbersome way of the process).

According to the current state-of-play, lump-sums are to be agreed during contract negotiations between the EC and the Consortium, meaning that actually incurred costs are no longer relevant and rules for eligibility and financial audits will become a thing of the past. Mind you, this does not mean that there will be no rules at all: the Grant Agreement will likely still specify who will do the work, what the grant attribution to international partners is and who are linked Third Parties and subcontractors. The Commission slides say that financial liability would be calculated based on each beneficiary’s share of the lump sum per work package.

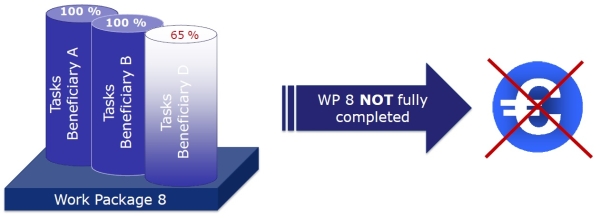

Analysing the available Commission presentations, I can follow and agree with most of their arguments for increasing lump sum project financing as a grant instrument, but there is one aspect which I find quite concerning. I am referring to the Commission’s notion that in future interim payments to funded consortia may not be paid at predefined points in time (except for the pre-financing of course), but only after specific milestones have been achieved. Mind you: in the Commission’s view a milestone is not like any of the milestones that we are used to in H2020 projects. No, in FP9 interim payments would be directly linked to the completion of a particular work package in the project. In practice this would mean that an interim payment would only take place:

- if ALL partners have declared that their individual share of the lump sum allocated to a specific work package has been used up;

- if ALL partners have declared that ALL of their activities in the work package have been fully completed, meaning that the work package as a whole is complete;

- the EC has approved the stated completion of the work package as a milestone.

So if a work package is not completed according to EC requirements in the Grant Agreement, the current view from the EC is that this will reduce the total grant amount and the consortium loses the share allocated to that work package.

Wow! Having been a H2020 project coordinator myself, I can just picture the additional consortium-internal tensions and fights an FP9 coordinator will be faced with. I give two examples below, but I am sure others will be able to think of more scenarios:

- In any project there will be work packages which will – by design – take longer to complete. I wonder how SMEs will be able to pre-finance a much longer stretch of company costs before they are reimbursed through the next interim payment? How to avoid that they plainly refuse to participate in work packages that take longer to complete? Could we then possibly be moving to a situation where academic partners start to act as lenders to their SMEs consortium partners just to keep them on board;

- What will happen if in a work package a partner (inadvertently) causes a significant delay in the technical completion of a given work package, with potentially a ripple-effect on subsequent work packages? Would the other consortium members not start to put so much pressure on this partner that it may be tempted to rush its work and thereby end up delivering a sub-par technical result?

All in all, the proposed structure for FP9 Interim Payments look to me as a recipe for more unnecessary tensions between consortium partners and can only harm the quality of the research innovation FP9 is supposed to generate. The Commission may think that a close link of payment to work-package completion will make projects finish faster, but show me evidence that there is (still) a significant number of H2020 projects that overrun their planned duration. In previous programmes (pre-FP7), long project duration extensions were approved fairly regularly, but we all know that in H2020 your chances of getting Commission approval for an extension beyond six months is already almost zero. I therefore fail to see why the schedule for interim payments cannot stay the way they are in H2020. To me, the risks of increased tension between project partners does not weigh up against maintaining a balanced management of collaborative projects. “If it ain’t broke, don’t try to fix it!”

Roy Pennings

(*) Please note that ‘lump sums’ already feature in a limited fashion in H2020. This article is based on presentations by the European Commission on the newly proposed Lump Sum Pilot in H2020 (and a revised Model Grant Agreement) which will then likely become the blueprint structure for FP9 lump sum financing.

“Horizon 2020 wordt een loterij”

Interview originally printed in the Dutch science newsletter “Onderzoek Nederland” (September 2015 issue, nr. 372) and based on an earlier article I wrote myself. In the interview I explain the real risk that getting H2020 funding under the Industrial Leadership and the Societal Challenges Pillars is starting to turn into a lottery. Many researchers – particularly those at the mid-stage of their career where the need to publish is highest – opt to participate in as many proposals as possible hoping that at least one will succeed. The solution to the problem for these pillars is to focus the evaluation not on scientific excellence, but on the participation of industry (e.g. Impact). After all: these specific pillars are meant to solve real-world problems and create real-world jobs for Europe. Only if proposals score equally on Impact the evaluators should consider scientific innovation to make a decision on who gets funded.

“Hoe de feedback verdween uit Brussel”

Interview originally printed in the Dutch science newsletter “Onderzoek Nederland” (June 2015). The interview (in Dutch) focussed on the lack and quality of feedback in Evaluation Summary Reports (ESRs) of stage-1 and stage-2 H2020 proposals. Right now, applicants do not get an ESR in stage-1. Why not, if the comments by the evaluators could make the proposal better in stage-2… And why so limited information in stage-2? How is an applicant to judge whether he/she should resubmit the proposal if the suggestions and comments for improvement are so vague? ESRs should help applicants, not confuse them, is my point.

ScienceBusiness conference on future of H2020

Commissioner Moedas talking about Open Innovation during the ScienceBusiness H2020 conference (Feb. 2016)

Last week, Brussels-based ScienceBusiness held its 4th edition of the Horizon2020 conference in Brussels. Central theme of the day was the concept of “Open Innovation” as the way forward in European research.

Commissioner Moedas shared the latest thoughts of the European Commission on the European Innovation Council (EIC). Other speakers (non exhaustive list!) were former CERN-DG Rolf-Dieter Heuer, who is now Chair of the EU Scientific Advice Mechanism and Jean-Pierre Bourguignon who is the President of the European Research Council. Nathan Paul Myhrvold, formerly Chief Technology Officer at Microsoft and co-founder of Intellectual Ventures, compared US and EU approaches to innovation and gave examples of how a more entrepreneurial attitude among the new generation of scientists is already radically reforming our economies and societies. Over 230 people from academia and industry participated in the conference. Several thousand people watched the live-stream!

In a separate workshop I moderated the ScienceBusiness Network meeting, where we shared best practices on H2020 research proposal development and implementation. The Network Members discussed ‘do’s & don’ts’ and identified possible improvements for the next Research Framework Programme (FP9). On behalf of the network I subsequently participated in the panel discussion with Robert-Jan Smits, the director-general of DG-Research at the Commission (see picture above). Smits outlined several changes to the further execution of the H2020 funding call programme as well as some further simplifications in the implementation of project, fow example on the use of timesheets. Smits admitted that despite the overall success of the programme and the endorsement of the application process by the European research community, there are still some significant improvements possible, in particular in relation to the evaluation process. Most Calls will in future follow a 2-stage process, whereby the aim of the Commission is that in the second-stage the success rate will be around 1:3. Following a question from the audience, Smits confirmed that he would re-assess the Commission’s earlier decision to scrap the so-called “Consensus Meeting”. The audience felt that the Consensus Meeting plays an important part in ensuring that the assessment of all evaluation panellists is taken into account before the final ranking. Smits also promised to check whether in future the Evaluation Summary Report can be a little more specific and detailed tan is currently the case.

The video-cast can still be accessed by clicking on this link: http://www.sciencebusiness.net/events/2016/the-2016-science-business-horizon-2020-conference-4th-edition/

Remarkable conclusions from High Level Expert Group on Economic Impact of FP7

(Please note that the article below is a personal opinion and does not reflect the view or position of any organisation I am working with/for).

(Please note that the article below is a personal opinion and does not reflect the view or position of any organisation I am working with/for).

Three weeks ago a High Level Expert Group published the ex-post evaluation of the 7th Framework Programme for Research, the predecessor of Horizon2020. The pan-European programme ran for 7 years, spending just about €55 billion euro across a multitude of interlinked research programmes. According to the report, 139.000 proposals were submitted, of which 25.000 actually received funding.

Whilst this report confirms what a great number of other reports have already said about the programme’s ability to advance science and create international collaborations, its assessment on the economic impact of the programme is – to say the least – remarkable.

Let’s start with a simple point. In report-chapter 6 called “Estimation of macro-economic effects, growth and jobs”, the Expert Group relies on two prior reports (Fougeyrollas et al. in 2012 and Zagamé et al. in 2012) to estimate that “…the leverage effect of the programme [stands; RP] at 0,74, indicating that for each euro the EC contributed to FP7 funded research, the other organizations involved (such as universities, industries, SME, research organisations) contributed in average 0,74 euro”.

What a statement to make: after all, everybody knows that in order to get access to FP7 funding, each organisation needed to provide a substantial cash or in-kind contribution. The Expert Group then continued by arguing that “…the own contributions of organizations to the funded projects can be estimated at 37 billion euro. In addition, the total staff costs for developing and submitting more than 139.000 proposals at an estimate of 3 billion euro were taken into account. In total, the contribution of grantees can be estimated at 40 billion euro”. Again, considering that organisations were required to chip in at least 30% of their own money to access the 70% of FP7 funding, one can only conclude that this amount was – in effect – a donation by these organisations and should not be confused with Actual Impact of the FP7 programme, as the Expert Group would have you believe.

But there is more: Using this flawed argument, the Expert Group subsequently draws the conclusion that: “The total investment into RTD caused by FP7 can therefore be estimated at approximately 90 billion euro”. Huh?! So if I take the €50 billion of FP7 given by the Commission and I add to that the contribution of applicant successful organizations (as the EC doesn’t fund 100%), I end up declaring that FP7 has contributed €90 million to the EU economy?! I don’t think so. Clearly, when doing their calculations, the Experts considered researcher salaries as the main metrics. This is confirmed in the report, as it says: “When translating these economic impacts into job effects, it was necessary to estimate the average annual staff costs of researchers (for the direct effects) and of employees in the industries effected by RTD (for the indirect effects). Based on estimated annual staff costs for researchers of 70.000 euro, FP7 directly created 130.000 jobs in RTD over a period of ten years (i.e. 1,3 million persons‐years).” If that’s the case, then why did we bother with FP7 at all… you could have achieved the same economic result by introducing a simple European tax reduction programme for employed researchers.

In fact, rather than the Expert’s grand conclusion that: “Considering both ‐ the leverage effect and the multiplier effect ‐ each euro contributed by the EC to FP7 caused approximately 11 euro of direct and indirect economic effects”, I would take the numbers to mean that thanks to the leverage effect and the multiplier effect, the European Commission managed to convince organizations during FP7 to give away 11 Euros for each Euro which it put into FP7. Furthermore, contrary to the Expert Group’s conclusion, I would at least argue, that their multiplier should then also have taken into account all the hours spent by applicant consortia writing proposals that did not get funding although they were above the funding threshold. As I showed in a previous article, the value of those hours amounts to roughly 1/5 of the total H2020 budget. In simple economic terms: their hours in service of the European economy could have been spent better.

FP7 wás a success: like no other research programme, it encouraged researchers from academia and industry alike to consider and test new ideas and start working together. The problem with FP7 was that ‘knowledge deepening’ did not (semi-)automatically mean that research results were then taken up by industry and translated into technologies and innovations. And that’s what FP7 to a large extent aimed to do. So in that sense, the only conclusion I can draw is that FP7 was a good effort. It’s most important achievement for me was that it paved the way for a new kind of thinking inside the Commission which put concrete and measurable impacts for science and society, for jobs and competitiveness at the centre. H2020 is the result of understanding that FP7 had some design faults which needed correcting. All the more interesting to read that Robert-Jan Smits’ (DG for Research at the Commission) solution for stemming the current tsunami of proposals now being submitted to H2020 is to put even more emphasis in the evaluation process on expected – measurable – Impact results. Go Commission!

H2020: Time to evaluate the evaluators?!

A few weeks ago the European Commission published a list with all the names of evaluators they used during the first year of H2020[1]. The list contains the names of all evaluators and the H2020 specific work programme in which they judged proposals (but not the topics!). In addition it shows the “Skills & Competences” of each evaluator as he/she wrote it into the EC’s Expert Database.

It’s not the first time the EC publishes this type of list, of course, but the publication comes at a poignant moment. As success rates for submitted proposals are rapidly declining and many researchers are wondering whether it is still worth developing anything for H2020 at all. In previous articles I already wrote about some of the main reasons behind this decline and possible solutions.

In this article I want to focus on the actual H2020 evaluation process, as for many researchers it is becoming very frustrated to write top-level proposals (as evidenced by scores well over the threshold and oftentimes higher than 13.5 points) and then see their efforts go under in short, sometimes seemingly standardised, comments and descriptions. Is it just the brutal trade-off between the increasing number of applications versus a limited budget, or do the evaluation comments and points hide another side to the process? Why are some people starting to call the H2020 evaluation process a ‘lottery’? Is there some truth to their criticism? How can the European Commission counter this perception?

I am sure most researchers have nothing against the EC’s basic principle of using a “science-beauty contest” to allocate H2020 funds. There is a lot of discussion however – also on social media – on selection process. Part of that discussion concerns the level of actual experience and specific expertise of those who do the selection. Simply put: Are the evaluators truly the most senior qualified experts in the H2020 domains they are judging proposals on, or is a – possibly significant – significant part of the panels comprised of a mix of younger researchers – using the evaluation process to learn about good proposal writing – and mid-level scientists who are good in their specific field, but also have to evaluate proposals that are (partly) outside their core competence?

Before I continue, please accept that this article is not intended in any way to slack off the expertise of people who have registered on the FP7 and H2020 Expert Database and have made valuable time available to read and judge funding proposals. I myself am in no position to make statements about what constitutes sufficient research expertise to be acceptable for peers when judging their proposals. The only point I will be making below is that if the EC wants to keep the H2020 evaluation process credible (and not stigmatised as a ‘lottery’), it needs to demonstrate to the community that it is selecting evaluators not just on availability but on their real understanding of what top-class research in a given research field means.

So let me continue with my argument: H2020 specifically states that it is looking for the most innovative ideas from our brightest researchers and developed by the best possible consortia. If that is the case, knowing that you cannot be an expert-evaluator if you are part of a consortium in that same funding Call, then already quite a few of the “best possible experts” will by default have disqualified themselves from participation in the evaluation process. It is also widely known that not all top-level experts want to involve themselves in evaluation either because to them it is not sufficiently important or because of other (time-)constraints. As a result, groups of typically 3-5 evaluators will typically consist a combination of real experts in that specific research domain and other evaluators who come from adjacent or even (very) different disciplines. So part of a given evaluation committee may therefore consist of – for lack of a better word – what I call ‘best effort amateurs’. Again: I have no doubt these are good researchers in their own field, but at this point they may be asked to judge projects outside of their core-competence.

Now you might think I am making these observations because I want to build a quick case against the evaluation process as it is. That’s not true. What I said above are views and comments that have been made by many researchers, on and off-stage, both from academia and inside industry. It’s thát feeling of unease and not knowing, that contributes to the more general and growing perception that H2020 is turning into a somewhat lottery-type process. For that reason alone, it is very important that the Commission now shows that their choice of combinations of evaluators is based on specific merit and not on general availability.

One way to refute the perception of a lottery, is – in my mind – for the EC to perform a rigorous analysis (and subsequent publication!) of the scientific quality of the people it used as evaluators. How to do that? A start would be to assess each evaluator against the no. of publications ánd the no. of citations he/she has in a given research science field. You can include some form of weighting if required to allow for the type and relative standing of the journals in which the publications featured. The assessment could also include the number of relevant patents of researchers. This should give a fairly clear indication on the average level of research seniority among the evaluation panels. One issue when doing this, will be that very experienced evaluators from industry may have fewer published articles, as the no. of publications is often considered less important (or even less desired) by the companies they work for. So the criterium of publications and citations should be applied primarily to academic evaluators. The same thing essentially also holds for patents, as ‘industry patents’ often are registered and owned by the company the researchers work for (or have worked for in the past). In other words: the analysis will probably not deliver a perfect picture, but as academics make up the majority of the evaluation panels, it should still give a fairly good indication.

Next step could be to check if the evaluators were actually tasked to assess only projects in their core-research domain or if they also judged projects as ‘best effort amateurs’. The EC could do that my matching the mentioned publications/citations/patents overview against the list of “Skills & Competences” the researchers listed in the Expert Database and the specific H2020 topics they were asked to be an evaluation panel-member in. Once you know that, you can also check if the use of ‘best effort amateurs’ happened because there just were not sufficient available domain-specific top-experts, or if the choice was based on prior experience with or availability of particular evaluators. I would find it strange, should that be the case. After all: the EC database of experts exceeds 25.000 names. The final step – in my view – would then be for the Commission to publish the findings – the statistical data should of course be anonimised – so that the wide research community can see for itself whether the selection of proposals is based on senior research quality linked to the H2020 proposal domain, or not.

I am sure that I am not complete (or even fully scientifically correct) in my suggestions on how to analyse the H2020 evaluation process. Things like the number of proposals to score and the average time spent on reading individual proposals will propoably also have an effect on scores. So what is the time-pressure the evaluators are under when they do their assessment and are there possibilities to reduce that pressure?

Please take this article as an effort to trigger further discussion that will lead to appropriate action from the EC in avoiding that our top researchers start dismissing H2020 as a worthwhile route to facilitating scientific excellence.

So European Commission: are you up to the challenge? If not, I am sure that there will be somebody out there to pick up the glove… I will be most interested in the results. Undoubtedly to be continued…

[1] http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/portal/desktop/en/funding/reference_docs.html#h2020-expertslists-excellent-erc